Architecture & Famous Architects

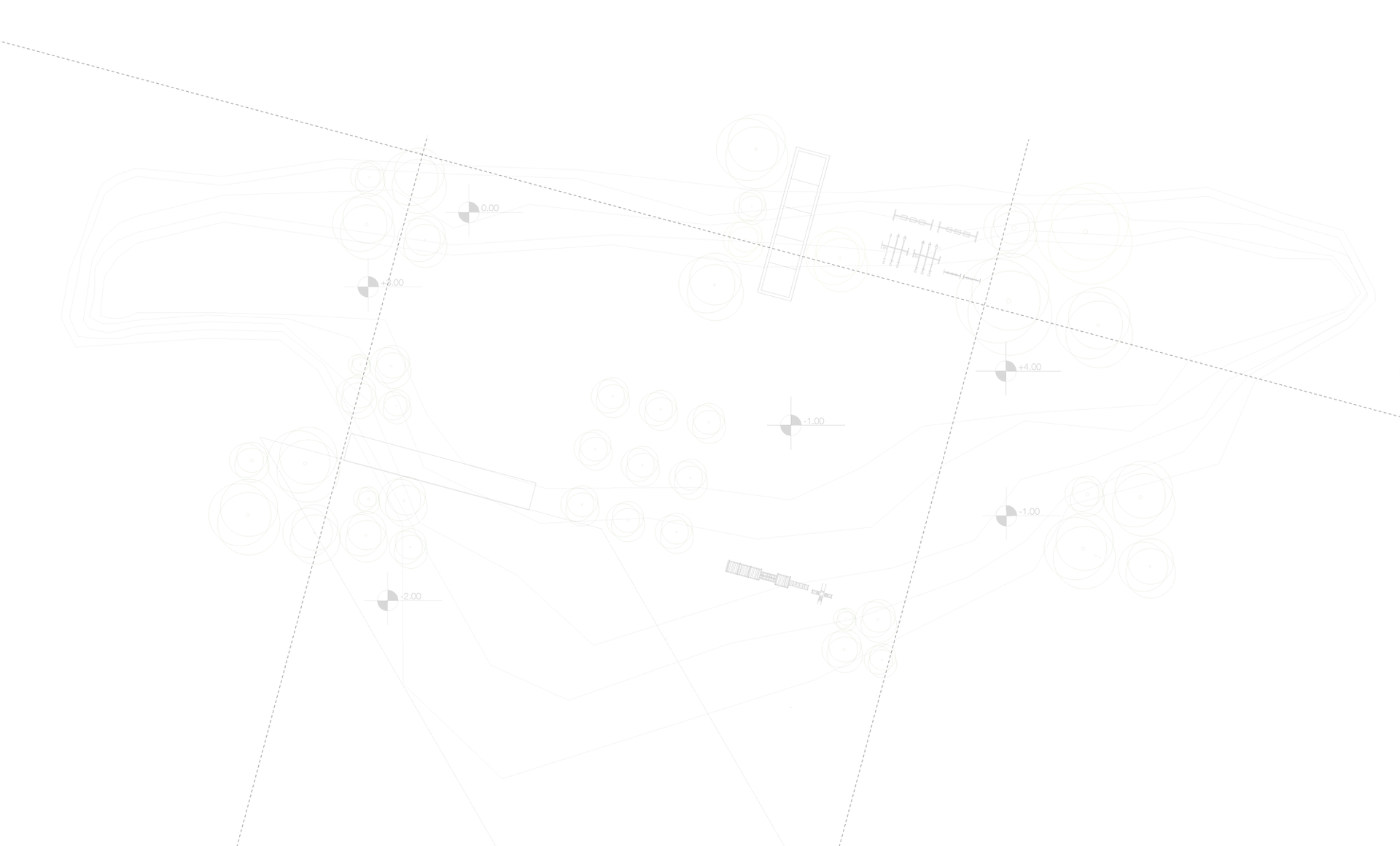

Clayton Way

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Behrens was a leading member of the Deutscher Werkbund, and through him Mies established ties with this association of artists and craftsmen, which advocated "a marriage between art and technology." The Werkbund's members envisioned a new design tradition that would give form and meaning to machine-made things, including machine-made buildings. This new "functional" design for the industrial age would then give birth to Gesamtkultur, that is, a new universal culture in a totally reformed man-made environment. These ideas motivated the "modern" movement in architecture that would soon culminate in the so-called International Style of modern architecture.

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, originally born Maria Ludwig Michael Mies was born March 27th, 1886, Aachen, Germany, and died August 17th, 1969, Chicago, Illinois, U.S., is a German-born architect whose rectilinear forms, crafted in elegant simplicity, epitomized the International Style of architecture.

Ludwig Mies (he added his mother's surname, van der Rohe, when he had established himself as an architect) was the son of a master mason who owned a small stonecutter's shop. Mies helped his father on various construction sites but never received any formal architectural training. At age 15 he was apprenticed to several Aachen architects for whom he sketched outlines of architectural ornaments, whichthe plasterers would then form into succo building decorations. This task developed his skill for linear drawings, which he would use to produce some of the finest architectural renderings of his time. In 1905, at the age of 19, Mies went to work for an architect in Berlin, but he soon left his job to become an apprentice with Bruno Paul, a leading furniture designer who worked in the Art Nouveau style of the period. Two years later he received his first commission, a traditional suburban house. Its perfect execution impressed Peter Behrens, then Germany's most progressive architect, that he offered the 21-year-ol Mies a job in his office, where, at about the same time, Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier were also just sarting out.

In Berlin Mies was influenced by Behrens' emulation of the pure, bold and simple Neoclassic forms of the early 19th-century German architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. It was Schinkel who became the decisive influence on Mies's search for an architecture of Gesamtkultur. Throughout his life, the elegant clarity of Schinkel's buildings seemed to Mies to embody most perfectly the form of the 20th-century urban environment. Another decisive influence was Hendrik Petrus Berlage, a pioneer of modern Dutch architecture, whom Mies met in 1911. Berlage's work inspire Mies's own love for brick, and the Dutch master's philosophy inspired Mies's credo of "architectural integrity" and "structural honesty." With regard to structural honesty, Mies would eventually go further than anyone else to make the actual rather than apparent or dramatized supports of his buildings their dominant architectural features.

During World War 1 Mies served as an enlisted man, building bridges and roads in the Balkans. When he returnes to Berlin in 1918, the fall of the German monarchy and the birth of the democratic Weimar Republic helped inspire a prodigious burst of new creativity among modernist artists and architects. Architecture, painting, and sculpture, according to the manifesto of the Bauhaus - the avbant-garde school of the arts just established in Weimar - were not only moving towrd new forms of expression but were becoming internationalized in scope. Mies joind in several modernist architectural groups at his time anbd organized many exhibitions, but there was virtually nothing for him to build. His foremost building of this period - an Expressionist memorial to the murdered communist leaders Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, dedicated in 1926 - was demolished by the Nazis.

Mies's most important work of these years remained on paper. In fact, these theoretical projects, rendered in a series of drawings and sketches that are now in the New York Museum of Modern Art, foreshadowed the entire range of his later work. The Friedrichstrasse Office Building (1919) was one of the first proposals for an all steel-and-glass building and established the Miesian principle of "skin and bones construction." The "Glass Skyscraper" (1921) applied this idea to a glass skyscraper whose transparent facade reveals the building's underlying steel structure. Both of these building designs were uncomprimising in their utter simplicity. Other theoretical studies explored the potentials of concrete and brick construction, and of de Stijl form and Frank Lloyd Wright concepts. Few unbuilt buildings surpassed them in the variety of ideas and in their influence on the development of the architecture of the time.

This influence was apparent at the first postwar Werkbund exposition at Weissenhof near Stuttgart in 1927. The exhibtion consisted of a housing demostration project planned by Mies, who had by then became the Werkbund's vice president. Europe's 16 leading modernist architects, including Le Corbusier and Mies himself, designed various houses and apartment buildings, 33 units in all. Weissenhof demonstrated, above all, that the various architectural fractions of the early postwar years had now merged into a single movement - the International Style was born. Though not a popular success, the exposition was a critical one, and Europe's elite suddenly began to commission modern villas, such as Mies's Tugendhat House (1930) at Brno, Czech.

Perhaps Mies's most famous executed project of the interwar period in Europe was the German Pavillion (also known as the Barcelona Pavillion), which was commissioned by the German government for the 1929 International Exposition at Barcelona (demolished 1930; reconstructed 1986) It exhibited a sequence of marvelous spaces on a 175- by 56-foot travertine platform, partly under a thin roof, and partly outdoors, supported bychromed steel columns. The spaces were defined by walls of honey-coloured onyx, green Tinian marble, and frosted glass and contained nothing but a pool, in which stood a sculptural nude, and a few of the chairs Mies had designed for the pavillion. These cantilevered steel chairs, which are known as Barcelona chairs, became an instant classic of 20th-century furniture design.

In 1930 Mies was appointed director of the Bauhaus, which had moved from Weimar to Dessau in 1925. Between Nazi attacks from outside and left-wing student revolts from within, the shool was in a state of perpetual tormoil. Though not cut out to be an administrator, Mies soon won respect as a stern but superb teacher. When the Nazis closed the school in 1933, Mies tried for a few months to continue it in Berlin. But modern design was as hopeless because of Hitler's totalitarian state, as was political freedom. Mies announced the end of the Bauhaus in Berlin late in 1933 before the Nazis could close it.

Four years later, in 1937 - again after working mainly on projects that were never built - Mies moved to the United States. Soon after he arrived in the country, he gained an appointment as director of the School of Architecture at Chicago's Armour Institue (later the Illinois Institue of Technology). Mies erved as the school's director for the next 20 years, and, by the time he retired in 1958, the school had become world-renowned for its disciplined teaching methods as well as for its campus, which Mies had designed in 1939-41. A cubic simplicity marked the campus buildings, which could easily be adapted to the diversified demands of the school. Exposed structural steel, large areas of glass reflecting the grounds o the campus, and a yellow-brown brick were the basic materials used.

The many commissions that his architectural office received after World War 2 gave Mies oppurtunities to realize large-scale projects, among them several high-rise buildings that are conceived as steel skeletons shethed in glasscurtain-wall facades. Among these major commissions are the Promontory Apartments in Chicago (1949), the Lake Shore Drive Apartments (1949-51) in that city, and the Seagram Building (1956-58) in New York City, a skyscraper office building with a glass, bronze, and marble exterior that Mies deignedwith Philip Johnson. These buildings exemplify Mies's famous principle that "less is more" and demonstrate, despite their austere and forthright use of the most modern materials, his exceptional sense of proportion and his extreme concern for detail. The International Style, with Mies its acknowledged leading master, reached its zenith at this time. The United States in the 1950s had a faith in material and technical progress that seemed similiar to the earlier German notion of Gesamtkultur. Miesian-influenced steel-and-glass office buildings appeared all of the United States and indeed all over the world.

Also during this period, Mies applied his modernist aesthetic to three more-intimate structures, the Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois (completed 1951), the Robert McCormick House in Elmhurst, Illinois (completed 1952; now part of the Elmhurst Art Museum), and the Morris Greenwald House in Weston, Connecticut (completed 1955). These were to be his only examples of domestic architecture in the United States.

In the 1960s Mies continued to create beautiful buildings, among them the Barcardi Building in Mexico City (1961); One Charles Centre office building in Baltimore (1963); the Fedral Centre in Chicago (1964); the Public Library in Washington, D.C. (1967); and, most Miesian of all, the Gallery of the Twentieth Century (later called the New National Gallery) in Berlin, dedicated in 1968. A heavy man, badly plagued by arthiritis, Mies continued to live alone in a spacious apartment in an old building near Lake Michigan in Chicago until his death in 1969. The IBM Building (1972), in Chicago, was completed after his death. Although Mies attracted a great number of disciples, his indirect influence was perhaps of even greater importance. He is the only modern architect who formulated a genuinely contemporary and universally applicable architectural canon, and office buildings all over the world echo his concepts. His work eventually came under criticism in the 1970s for rigidty, coldness, and anonymity, but it was Mies's declared choice to accept the nature of 20th-century industrial society and express it in his architecture.